Know Your Historical Context

I recently turned 30. For a lot of people, capping off another decade like this can a pretty sobering experience.

For me? Eh. I saw it coming.1 Back when I turned 27, I remember noticing that the addition of one year caused people to change from rounding down to 25, to rounding up to 30. “I’m not old yet,” I thought, “but I do think I’m running out of youthfulness.”

But there’s a silver lining to all this: I now have more social license to be the grouchy old man that I was always meant to be. “Get off my lawn!” I’ll shout, assuming I can ever afford a house big enough to have a lawn.

So I’ll start now with one example: it’s really striking how things that you saw develop over the course of your life end up being taken for granted by those who are younger. For them, this is the way things have always been. For you, you can trace it back through your memories: these were decisions that were made in a specific historical context, and have been maintained due to inertia even when the context for them breaks down.

So in this article, I want to focus on a specific example of this from the tech world, that I’m surprised people don’t talk about more explicitly:

Twitter’s character limits.

Twitter’s a bit of a weird social network. You can write text, but the text is limited in length to only a short few sentences. You can post images and videos, but it’s not strictly focused on images like, say, Instagram. The vast majority of Twitter is completely public, which is surprising in a modern internet ecosystem that has been made severely aware of how much privacy matters.

I’ll get the elephant in the room out of the way right now: I don’t like Twitter much. I’m the kind of person who likes nuance, who likes having a deep back-and-forth with someone who holds a different opinion than me.2 Twitter’s format doesn’t lend itself well to that. Replies are all public, encouraging people to dogpile. The short character limits mean that it’s harder to communicate context and subtlety, encouraging flippant retorts instead of deeper explanations. It got so bad after the 2016 US elections that I quit Twitter almost entirely—restricting myself only to tweets announcing new posts on this blog—and only announced that I had done so nearly two years later.

In case it wasn't obvious, I don't think this account has much life left in it anymore. I'm finding that Twitter isn't really a good use of my time, nor is it really a good communication medium for the kind of communication I prefer.

— Gabriel B. Nunes (@Kronopath) April 5, 2018

The short, 140-character limit was one of the things that most drove me away from the platform. I’ll admit that Twitter has been making some good changes since I left: they doubled their character limit from 140 to 280 characters in 2017, and made it a lot easier to both post and follow multi-tweet threads. These days, you get people posting what amount to short essays on Twitter, broken up into a few sentences per Tweet. It’s still not enough to bring me back there—I think I’m just too verbose for Twitter—but I’ll admit it’s an improvement.

But the question remains: why was it like this in the first place? Why so few characters?

For that, we have to go back.

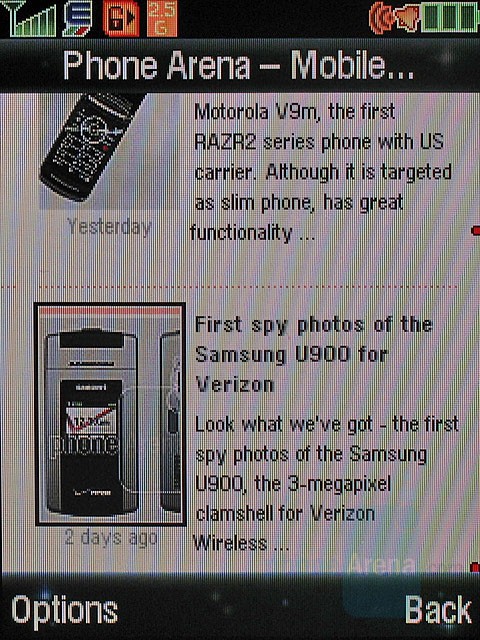

Twitter was founded in 2006. This was before the iPhone, which only released in 2007. Smartphones existed then, but they were generally BlackBerry phones used by business professionals to answer their work emails on the go, and weren’t popular with the average consumer. To give you a sense of who the target market for smartphones was back then, one of the big criticisms of the original iPhone was that it didn’t have a physical keyboard and thus was unsuitable for composing emails and Microsoft Word documents. The average person had a phone more like the Motorola KRZR.3

Contrary to popular belief, the mobile internet actually did exist back then: even the KRZR had a browser. The problem is that the mobile internet was slow. Absurdly slow. To compensate for this, most phone browsers at the time displayed a much-reduced version of the internet. I’m not talking about the kind of mobile sites you get today: I’m talking about web browsers that displayed only the text of the webpage, with the layout absent or reconfigured to fit the low-resolution screens. If they showed images at all, they compressed them down to tiny sizes. The big draw of the iPhone’s web browser was that it promised to show full web pages, the same as you’d get in a desktop browser, with panning and zooming to allow for navigation of desktop sites on its smaller screen.

This image is from a newer version of the KRZR’s browser, and believe me when I say that even this is significantly better than what my old KRZR had. Note that the article I took this image from touts that this new model has a “full HTML browser”. The old ones didn’t, and displayed only the text of the page!

Blogs were reasonably popular, and social media was already on its rise, but people used both of those services almost exclusively on desktop browsers. Even if you were one of the early adopters of the iPhone, mobile data was still very slow, and websites weren’t yet optimized for the smaller screens of mobile browsers. And mobile apps? Forget about it: the iPhone didn’t have third-party apps or an app store until 2008.

So along comes Twitter, calling itself a “micro-blogging” service, with generally the same weird limitations it has today. Why did it become so popular?

Twitter in 2007, courtesy of the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

Picture you were a tech journalist in 2007. Say you were attending Apple’s WWDC conference, and you wanted to give your readers live updates for Apple’s keynote where they were announcing their new operating system. Remember: streaming video wasn’t really easy or common back then, so people were depending on journalists like you to know exactly what was announced as soon as Apple announced it. Your website probably used Wordpress or some other heavyweight CMS, so keeping an article updated would usually require you to haul a laptop to the conference, and hope that the conference wifi doesn’t flake out due to all the other journalists connecting to it.

But then you notice Twitter. Its big selling point was actually SMS integration: you could post Tweets, add or remove followers, and receive updates, by texting Twitter’s phone number. You didn’t even need a smartphone! A flip phone worked just as well. And so you could tell your readers to watch your Twitter account, or maybe even embed your Twitter stream in an article, so they could get minute-by-minute updates live.

In short: Twitter was the first mobile social network, done via some clever adaptations of existing SMS technology.

This video, surprisingly, is from 2013, and yet it already feels like a relic.

But adapting that technology also meant adopting its limitations. Text messages have a limit of 160 7-bit characters. And back then, concatenated SMS wasn’t commonly supported either. Since Twitter wanted to display your messages via SMS to your followers, your tweets had to fit in an SMS: 140 characters per tweet, with the remaining 20 characters reserved for metadata like the person’s username.

This SMS service has since been discontinued in most countries. There were some security bugs with the service, some of which were hilarious, and with the advent of Twitter’s mobile app, I’m sure the service had been seeing dwindling usage over time. But the character limits remain.

I’m surprised just how rarely people talk about the legacy behind this decision. It feels like people treat it as a fact of life, that it defines the character of the service, that it decreases verbosity, whatever. Even their CEO: in this early 2016 tweet, though he briefly mentions the original reason for the limitation, he then calls that restriction “beautiful”… in a tweet that contains a picture of text.

— jack (@jack) January 5, 2016

I don’t think it’s beautiful. And I think, at some point, he stopped believing that as well. I think the toxicity of the conversations on Twitter in the US during late 2016 showed him that there were improvements to be made. The doubling of the character limit happened the following year. And despite people’s concerns that it was going to increase verbosity, despite the fact that I haven’t got back on the service, it seems like the effects of that change were positive.

Can you imagine what it would have been like if we had gotten those improvements before the 2016 elections?

Think about the structures around you, the systems you work with on a day-to-day basis, and the laws that you live under. Do you understand why they exist? Do you know the context in which they were originally built? Are they still achieving their original purpose?

When talking about long-standing traditions and systems,4 people often cite Chesterton’s Fence. Say there’s a fence in the middle of the road, and someone wants to get rid of it.

The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

In short, if you don’t know why it’s there, chances are it’s serving a purpose that you don’t understand.

The flip side of that, though, is that if you do understand why something is there, and what the effects of it are in our current time, then you should feel empowered to make reforms. This goes doubly true for decisions that were made for historical reasons.

These kinds of decisions feel especially prominent in the United States. Let me give two examples that I’ve had to deal with since moving here.

US healthcare is a mess. Employers buy expensive insurance for their employees and offer it as a benefit alongside their salary. Because the people buying the insurance are not the people using it, insurance companies don’t invest in simplicity and usability of their systems. Trying to find a doctor here in the United States is difficult, because it requires either making several phone calls to clinics and insurance companies trying to find out which doctors are in-network and what the costs will be, or it involves wading through poorly-made and confusing insurance websites.5 More likely, it’ll end up being both. Good luck doing that when you’re sick with a fever.

Even if you do manage to figure out how to deal with your insurance, then you have to worry about losing your job. Obviously, being unemployed means you may lose your insurance. But even if you manage to find a new job, you’ll have to figure your healthcare out all over again, as you change insurance companies and find new doctors in the new networks. And if you’re a contractor? Too bad, you get nothing. Hope your contracting rates are high enough that you can pay the cost of health insurance yourself. (If you’re driving for Uber, they won’t be.)

This is the worst of all worlds. It’s not a public medical system like they have in Canada. It’s not a good capitalist system, because it falls victim to the third-party payer problem for both health providers (which the insurance company pays for) and insurance companies (which employers pay for). It’s just bad, regardless of your political orientation.

And the main reason it became popular is because it was a good way to work around high tax rates and wage freezes during World War II, allowing employers to de-facto increase compensation without the employees falling prey to high tax rates.

US immigration law is another subject I've been forced to get comfortable with. At some point, I plan to write more about it. For now, let me briefly compare the system that Canada has for obtaining permanent residency to the one that the States has, specifically for high-skilled workers.

In Canada, you can apply for what they call Express Entry. Effectively, they ask several questions about you and each of those questions awards you a set of “points”. Paraphrased, the questions are things like:

- Do you speak one of Canada’s two official languages? (And are you willing to take a test to prove it?)

- Do you have family in Canada?

- Do you have a degree from an officially recognized university, either in Canada or abroad?

- Do you have work experience in any in-demand fields?

…and so on. With enough points, and documentation to substantiate them, you can apply for permanent residency and be reasonably sure you’ll get it within about 5-6 months.

The US has no such system. You have to obtain permanent residency either by being sponsored by family, as a refugee, by winning the diversity visa lottery, or by being sponsored by your employer. The latter is what I went through, and it was a long process. For me, it took over a year and a half, and I was one of the fastest cases. If I had been born in India or China, I could be waiting several years, if I ever got it at all.

If you’re being sponsored by your employer, the entire process revolves around you and your job. Your employer has to prove that there’s no existing American citizen or permanent resident that can fill your current role (by literally posting a job listing for your position). You have to provide letters of reference to provide evidence that your experience fits that role. If you change jobs, you have to start that part of the process all over again, adding another six months to a year to your application. I’ve even heard from friends that it’s a bad idea to leave a job within six months of getting an employer-sponsored green card if you’re planning on applying for citizenship, because it could negatively impact your citizenship application.

This has all the hallmarks of a system that was created when people kept jobs for decades, a trend more common in the era immediately following WWII. It sends a message to those going through it: you’re being brought to this country for this job. Your value to the country is in filling this corporate role, and that’s the only reason we’re letting you in.

Of course, these days, keeping a job that long is practically unheard of. Tech companies that do well manage to retain employees for an average of 2-3 years. With employees being so much more mobile, a system more like Canada’s makes way more sense: bring good people into the country and trust them to make their own way within it.6

Like Twitter’s character limit, these were decisions that fit their time well. But the world changed and moved on, and these ossified systems have started to chafe against the structure of the world we now know.

Chesterton was right: if you don’t know why a fence is there, don’t remove it yet. Instead, try to track down the reason the fence was built in the first place, then evaluate whether the assumptions that were made back then still apply today.

And if they don’t apply, and if the fence is causing problems, then you shouldn’t hesitate to tear that thing right out of the ground and replace it with something better.

-

That said, I didn’t expect that I’d be celebrating it quietly during a massive pandemic, but I won’t get into that in this article. We’re all living through this, I’m sure you don’t need me to tell you about it. ↩︎

-

And who, admittedly, is sometimes too verbose for his own good. ↩︎

-

Average people like me, in fact. Mobile data in Canada was expensive enough, and I was enough of a cheapskate, that I clung onto a combination of a KRZR and an iPod Touch for many years before I finally got myself an iPhone. ↩︎

-

Twitter, admittedly, is likely one of the least long-standing of these systems. That’s why I think it makes for a good example, actually: these decisions were recent enough that even people my age can still relate to the way the world was back then. ↩︎

-

True story: a few days ago I had to help my girlfriend deal with a minor but urgent medical problem. But the insurance company had taken their entire website down for maintenance, including all their verification, login, and search systems. In the middle of a pandemic. We weren’t able to find proper health care until the following morning. ↩︎

-

Even one of my most hated politicians has come out in favour of a more Canadian-like system, and it’s one of the few things that’s ever come out of his mouth that I’ve found myself agreeing with. Of course, he never actually went through with it, choosing instead to cause problems for almost every immigrant in the United States. And I doubt I would trust him to implement it properly without adult supervision. ↩︎